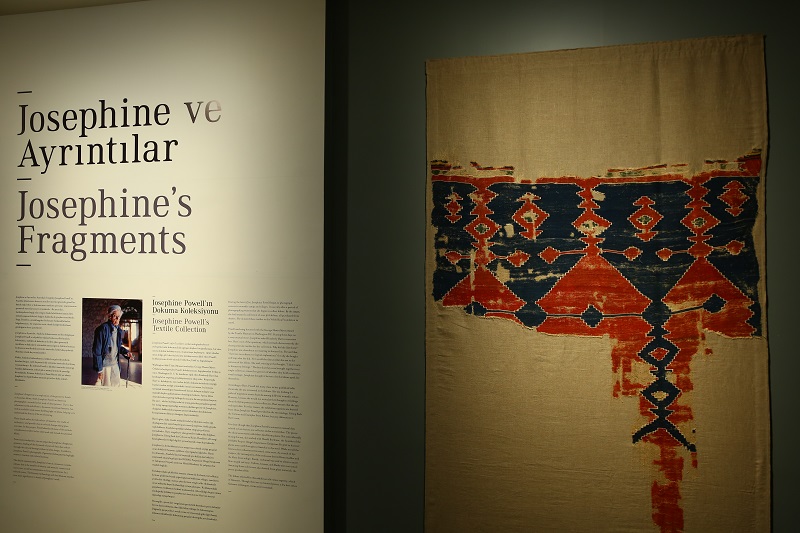

Josephine’s Fragments

The cradle of civilization, Anatolia, reflected in the fragments and provides cues to cultural changes taking place over time. Josephine Fragments emerge as an alternative standpoint on thousands of years Anatolian culture through Josephine Powell’s lens. The exhibition brings a chance to observe the substantial parts of geometric patters becoming cultural heritage and women’s creativity over the years.

The culture, transfer of identity and memory, has been transmitted different perspectives through one’s roots to future generations in history. The memory of the kilims that has been carried out by Josephine’s photography will arouse with its new and alternated representation, even more significance in Erimtan Archaeology and Arts Museum which is surrounded by these archaeological and artistic scope.

On Josephine Powell

Josephine Powell, an American photographer ,born in 1919 in Manhattan and left the United States following the end of World War II. As a self-taught photographer, she photographed in Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, North Africa, and Iran for two decades before moving to Istanbul. During that time, she created an extensive body of black and white imagery of remote places, the people living there, and remnants of historical buildings. Many of these photographs were published in works on art and architecture.

She often photographed the objects in situ before including them in the collections, providing valuable visual information on the use of everyday handcrafted goods. In addition to being a photographer, she became a collector, amassing more than 400 Anatolian kilims and thousands of everyday objects once common in Anatolia, such as spinning wheels, threshing sleds, and spindles.

Josephine’s interest in kilim design does not travel the well-worn speculative path of an encoded language of design but rather considers patterns as a means of tribal communication. In her talks and published works on nomadic women weavers and their textiles, she considered kilim patterns as a form of tribal identity. Josephine regarded these patterns as an expression of a deep tradition which superseded the personal expression of an individual weaver. Thus, the language of pattern she was interested in was collective, rather than individual.